Questions of Matrimony

In early modern England, options for settling marital disputes were limited. The first divorce with permission to remarry was obtained by a private act of Parliament in 1670, but this was a route open to very few.

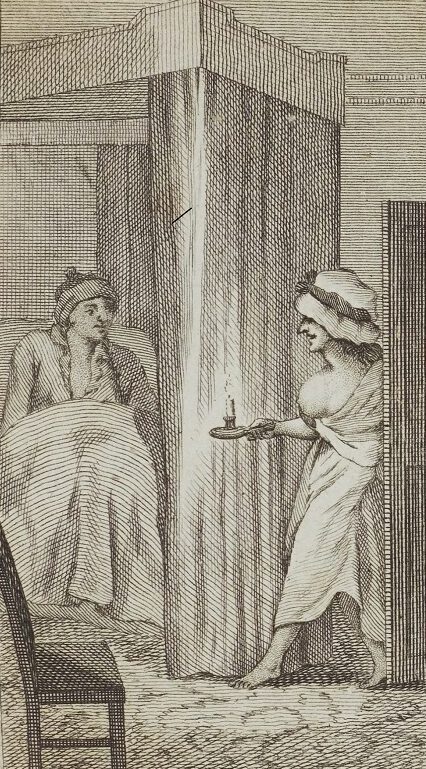

Amongst the poor, the usual choice for a man escaping a failing marriage was to abandon the family home, leaving wife and children at risk of destitution. For a wife, the options were even fewer, as, with children in tow, she lacked the employment opportunities available to her husband.

Those with more resources might turn to the ecclesiastical courts, as the Church held jurisdiction over marriage and sexual behaviour. These courts had the authority to grant a separation ‘from bed and board’, which they might do on grounds of infidelity and cruelty on the part of the husband, or infidelity alone on the part of the wife. Such a separation did not permit remarriage. A subsequent union was only permitted if the first was annulled.

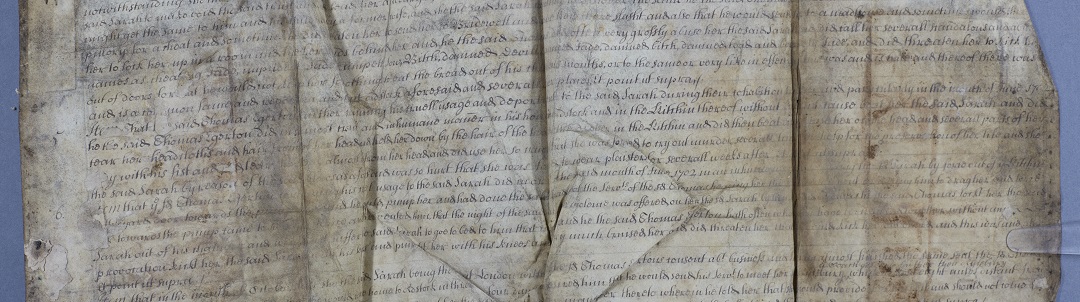

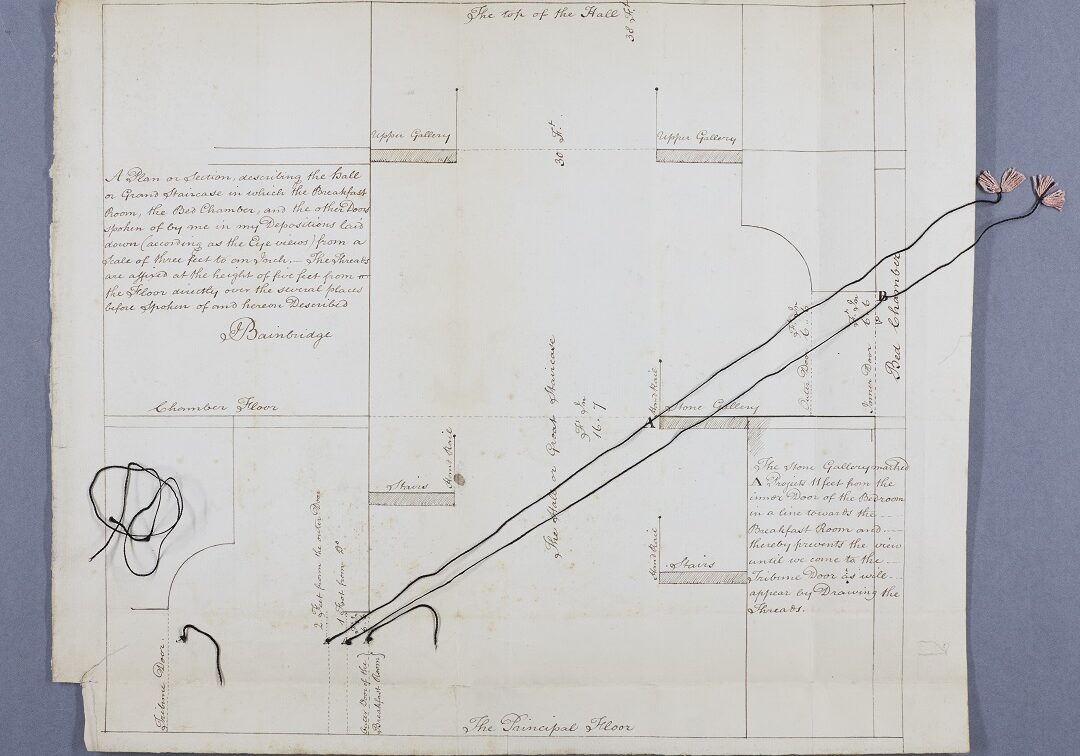

Most cases arriving at the Court of Arches had already played out in diocesan courts, making them both vastly expensive and excruciatingly public. Nevertheless, over eight hundred Arches cases between 1660 and 1857 relate to separations.