This exhibition drew on the Library’s rich holdings of prints, maps and plans to give an insight into how Lambeth has changed from the 17th to the 19th century. The area’s social and economic history was shown through depictions of Lambeth marsh and the pre-Embankment Bishop’s Walk, the growth of the pottery industry, as well as new streets and pubs around Waterloo station. The development of Lambeth Palace and its estates is also featured from woods in Camberwell to Timber yards in Waterloo. The final part of the exhibition contained images from the archives of the Church Commissioners and broadens the scope to the 1960s housing estates of Park Hill, Croydon and Hyde Park. Following Lambeth’s rural to urban transformation, this provides an interesting contrast in presenting the post-war ‘village concept’ in modern London.

The exhibition ran from 8 August to 6 October 2022.

Topography of Lambeth

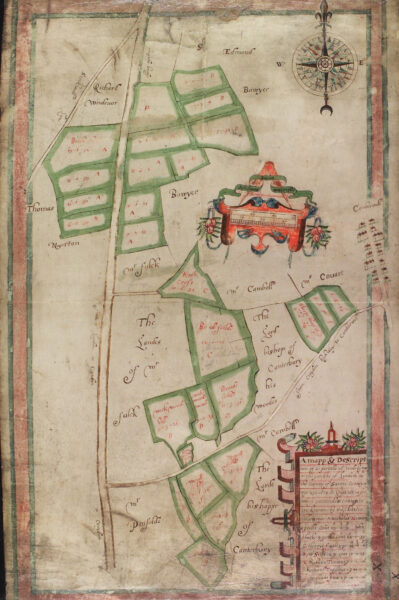

Lambeth Palace Library holds a rich and varied collection of maps, ranging from 16th century atlases, through 19th century tithe and estates maps, up to prints illustrating the most recent changes in parish boundaries.

Maps can provide a valuable source or finding aid for a variety of research relating to architectural and urban history, local history and the changing relationship between the Church and the society it served.

Marsh and River: Pre-modern Lambeth

The area now known as Lambeth has been associated with the Archbishops of Canterbury since at least 1190, with the first Lambeth Palace constructed from 1197 onwards. Until the mid-18th century, much of the current borough was marshland and sparsely inhabited, with access to Westminster and the north side of the Thames afforded by a horseferry. Prior to the construction of the Albert Embankment in the mid-19th century, a shady path known as ‘Bishop’s Walk’ stood between the Palace and the river.

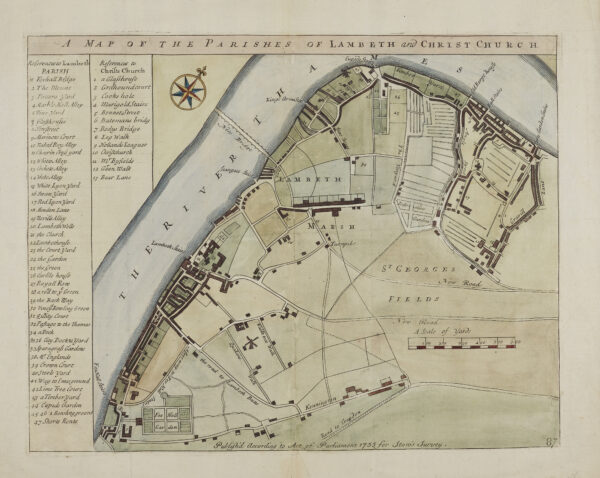

A Map of the Parishes of Lambeth and Christ Church, Prints 016/026

Hand-coloured engraving, 1755. From the sixth edition of John Stow’s and John Strype’s Survey of London (1754-1755).

This map has many features you may recognise today, although the names might have changed. Vauxhall takes its name from Sir Falkes de Bréauté, whose house became known as Falkes Hall, then Fox Hall as shown. Lambeth Palace is curiously referred to in one word as ‘Lambethouse’. The ‘New Bridge’ is the first Westminster Bridge, opened in 1750 and then replaced in 1862. The ‘Glasshouses’ prefigure the present-day street Glasshouse Walk and Walnut Tree Walk is another surviving link to the area’s pre-industrial past.

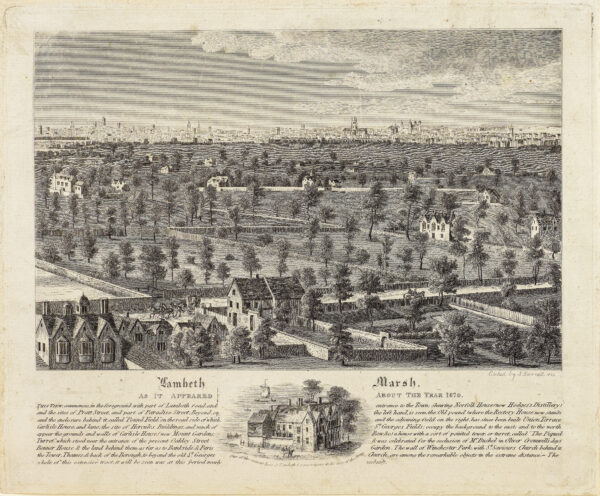

Lambeth Marsh, Prints 014/031

Etching by John Barnett, c. 1820. ‘Lambeth Marsh as it appeared about the year 1670’.

This print shows a 17th century view of the Lambeth Marshland. In the 18th century portions of the marsh were drained, and inhabitancy of the area increased. Much of the land was owned by the church and sold off in small pockets during the 19th century. The area’s swampy history is still reflected in some local street names, notably ‘Lower Marsh’.

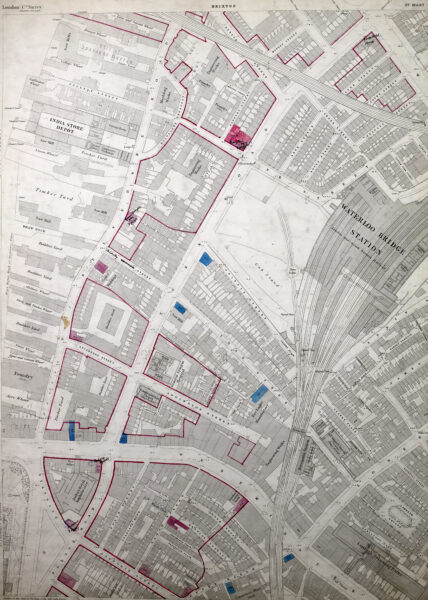

Pottery, protest, and a refurbished Palace: Change in the 19th century

Lambeth became increasingly urbanised through the 19th century, particularly with the advent of new transport links and industrial activity. The construction of Waterloo Bridge, opened in 1817, facilitated links with other parts of the city, and factories such as Doulton & Co. brought new workers into the area. Increased working-class presence was reflected in political activism in the area. One of the last and largest Chartist movement meetings was held on Kennington Common in 1848. Lambeth Palace itself also changed dramatically, with a major renovation and augmentation to the existing buildings commissioned by Archbishop Howley.

Cuper’s Gardens, Prints 016/023

Engraving by B. Howlett, 1825. View of Cuper’s Gardens and map showing Waterloo Bridge Road.

The small pleasure garden known as ‘Cuper’s Gardens’ (sometimes ‘Cupid’s Gardens’) opened in the 1680s, having been established by Abraham Boydell Cuper, gardener to the landowner, the Earl of Arundel. As with the larger Vauxhall Gardens, there was an entry fee. Visitors could enjoy entertainments such as orchestral concerts and firework displays whilst promenading. Unfortunately, Cuper’s Gardens attracted some unsavoury visitors and became known as a spot for pickpockets and loose morals. The attraction closed around 1760. In 1813, some of the land was bought to use for the approach road to Waterloo Bridge, which opened in 1817. The new St John’s Church, Waterloo, which opened in 1824, is also shown.

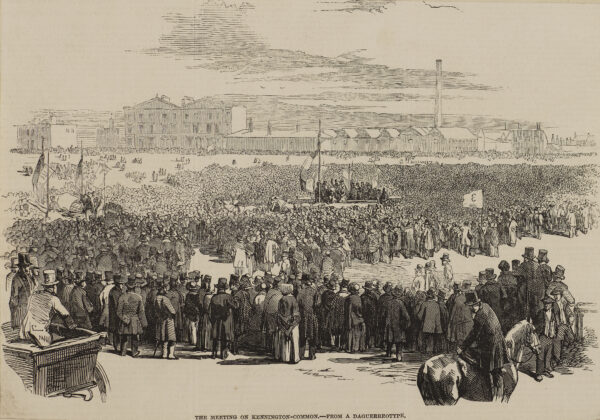

Chartists on Kennington Common, Prints 020/024b

Wood engraving from a daguerreotype, 1848. ‘The meeting on Kennington Common’. From The Illustrated London News, April 15, 1848, p. 242.

This image shows the crowds present on Kennington Common for a Chartist meeting in 1848, one of the last and largest meetings of the movement. Between 20,000 and 50,000 people assembled on the Common on the morning of 10th April, intending to march to Westminster and deliver to Parliament a petition, claimed to have more than 5 million signatures. The petition stated the movement’s demands on male universal suffrage, voting by secret ballot, and other democratic reforms. Despite Government fears to the contrary, the day turned out to be uneventful; marchers were peaceably turned away from Westminster Bridge by special constables. The petition lost credence and was rejected when it was discovered to have many false signatures. This image is reputedly the first wood engraving based on a photograph and published in a newspaper.

Church Estates

The Church owned property which could be used as premises for its various activities such as worship, education, accommodation of the clergy and as a source of income for the clergy, maintenance of buildings, education and evangelistic activities and administration. Some church bodies had their own endowments of property including bishops, deans, chapters and other offices of cathedrals and collegiate churches. Following the establishment of the Ecclesiastical Commissioners (EC) in 1835, these estates were gradually transferred to the EC to be managed as a national asset on behalf of the Church as a whole. Now, estates still owned by the church are managed by the Church Commissioners, a body created after the merge of the Ecclesiastical Commissioners and Queen Anne’s Bounty in 1948.

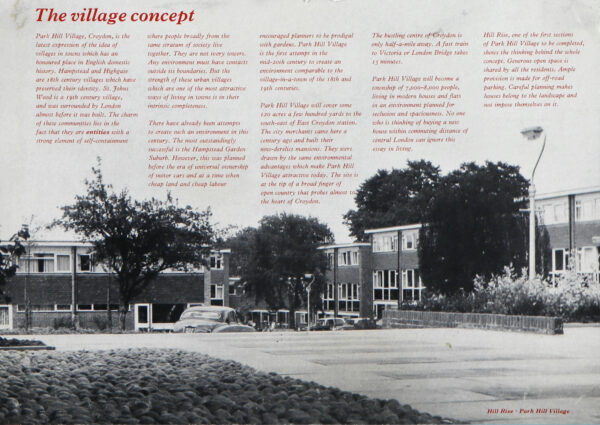

Images displayed here particularly focus on re-development of urban estates in London in 1960s. At the time, replacement of the old architecture with modern, often brutalist buildings was welcomed and seen as a sign of progress and positive change and a way of solving post war housing shortages. The phenomenon was later called ‘the era of radical concrete’.